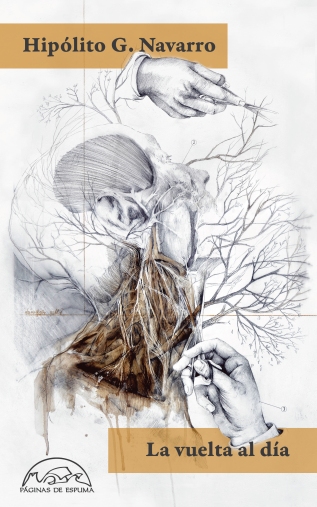

La vuelta al día (Around the Day)

La vuelta al día (Around the Day)

Hipólito G. Navarro

Páginas de Espuma, 2016, pg. 251

La vuelta al día (Around the Day) is Hipólito G. Navarro’s 2016 return to print after a long, eleven year absence. Navarro is a Spanish writer, mainly of short stories, who has been one of the seminal short story writers who began publishing in the 1990’s. His 1996 collection El aburrimiento Lester (The Boredom, Lester) is a virtuoso exploration of the short story form, both in terms of style and structure. He latter followed up with Los tigres albinos (2000) and Los últimos percances (2005), each of which continued his explorations of the short story form. (I’ve reviewed all three works here and his collection El pez volador, which takes stories from each of these collections.) Given the long absence from publishing, La vuelta al día is a much anticipated work.

At the core of much of Navarro’s work is humor. It is often dark or colored with a sense that the joke is some misfortune of one’s own making that is impossible to escape. Even in the length introduction to the collection he remarks that his mother, when he gave her a copy of his last book, Los últimos percances, as she was dying said,

¡Los últimos percances! ¿Por qué no le has puesto penúltimos, al menos?

The last misfortunes! Why didn’t you call it the penultimate, at least?

You most often see this sense in the Navarran unfortunate, usually it is the narrator, but occasionally it is just the main character of the story. The Navarran unfortunate is a man (it’s never a woman, although they can be the narrator) who through some obsession, large or inconsequential, has screwed up somehow. They are aware of the mistake and describe themselves in self depreciating tones that both show an acute self awareness and a deep fatalism about their future. Generally, the unfortunates reveal this desperation in a wildly verbal prose full of racing thoughts that are hard to control. Navarro is a rich stylist of the language and uses these monologues to full effect. Some of the unfortunates have a happier ends, but even they know that they are idiots and lucky to have gotten what they did.

In the latter category falls Ligamentos (Ligaments). A kind of love story, the narrator has an injured leg, but he meets a friend of a friend and is so taken with her he goes on a long walk with them in the woods. He knows nothing about nature, but he fakes as much as he can. The humor comes in his confessions to the reader about how little he knows about the world and his desperate, boyish attempts to keep up with her on the walk, which results in his further injury. The narrator is self aware of how silly he is, how every thing he does makes him even more ridiculous, and it gives him a sacrificial charm when finally wins her admiration by covering himself in remnants of the forest floor.

Verruga Sánchez takes the self obsessed male even further. Narrated by Sánchez’s wife, it’s the story of a Professor who is extremely popular with his students and well respected with his colleagues. The only issue is he has a distinctive mole near his eye. He can’t stand it any finally has it removed. Of course, it doesn’t go as he wishes and looses the adulation he’d grown accustomed too. He mopes around on the couch. It’s his wife who tries, unsuccessfully, but loyally to get him to forget it. It’s dark without the usual self pity: vanity allows no self reflection. Sánchez, like all of the unfortunates, has brought this on himself and has paid the price. What is notable is this is one of Navarro’s female narrators. It stabilizes the story, keeps the manic obsession at bay and makes it even sadder to know she still loves him.

Included are three much darker and riskier stories that I think may have gotten away from Navarro. La escusa termodinámica (The Thermodynamic Excuse) is narrated by a cuckold who’s wife has gone to a cabin in the woods with his brother. The desperate rant is a series of questions that the narrator asks himself about why he couldn’t start a fire. On its own the story has commendable aspects. Its when you get to something like Las estampas del timo with its light harted story of infatuation that includes incest, though, all these men become a little too much. Where it is the most distributing is the ultimate unfortunatein En el fondo de la memoria (In the Depths of Memory). Here Navarro creates his most manic character, a man who is pacing his small apartment, describing it as a kind of cell as he waits for his wife to bring her son home. The son does not live with them and he has never met the child. Yet he is afraid of the boy because he knows he is the father: he was the one who raped his wife. It is such a complicated statement, one that opens so many questions, some of credulity. I’m still not sure I can even contemplate the idea that the woman he raped would not know it was him somehow, or hadn’t seen the likeness already.

Whatever the case, all these stories give much of the collection a male-centric view of the world that is both self pitting and self obsessed, and leads to self destruction. When done right, as in Ligamentos and Verruga Sánchez, they are tragicomedies; when they misfire they are off putting.

Even though the Navarran unfortunate is heavily present, the real standouts, are his elegiac stories, stories that look to the past and find a restrained melancholy. The two standouts are El infierno portátil (The Portable Hell) and Tantos Veces Huérfano (So Many Times an Orphan). The former is the memory of a boy who worked in his grandfather’s blacksmith shop. Some nuns come down the hill from the convent to ask for hand outs. He notices the younger nun and as they look at each other for a moment he finds himself attracted to her. The story is handled deftly, the attraction is brief, subtle, as is the punishment the boy thinks he receives when the nun leaves. He is able to capture the sense of something new and uncontrolled in the briefest interlude. It’s in the unguarded moments that these realizations come.

Tantos Veces Huérfano, for me, is the best story of the collection. In it an old man remembers a journey to his father’s home town for the arrival of electric lights. It’s an awakening both in terms of sex and violence, all happening within his extended family. And it’s as memory is, unclear. Why was his father murder? The narrator doesn’t know. It’s the strength of the story that the narrator’s memory comes and goes, and an exact clarity of the events is illusive. Along with La vuelta al dia and La poda y la tala de los arboles (The Pruning and Triming of Trees), there is a sense of the past as both something alluring and melancholic, a place one would like to be, but a world that not only doesn’t exist, but in which one does not belong.

Finally, if humor and great verbal ability are two hallmarks of Navarro’s writing, the last is a playfulness. Los k (The ks) is a perfect example of this. The ks refer to kilobytes and the narrator imagines them as living creatures who have a mind of their own. They escape and he loses part of his novel. With this comes the sense that writing is something alive, something not only exists, but has its own independent life. He’s used stories like these to explore the short form and his earlier work was marked with this playfulness. In La vuelta al día we get a glimpse of this skill. I wish there had been a little more of this as they are delightful.

In all, the collection is a welcome return publication. There were certainly some misfires. The stories that dealt with the past were the strongest and most compelling, while those of the Navarran unfortunates show that Navarro is still in command of his verbal powers. Hopefully, it won’t be eleven years for the next collection.