Cinco horas con Mario (Five Hours with Mario)

Miguel Delibes

Note: this book was translated into English sometime in the 80’s, but I can’t speak to its availability.

Miguel Delibes was one of Spain’s most important writers during the last half of the 20th century. Cinco horas con Mario (Five Hours with Mario), published in 1966, was one of his major works and a huge success when published. It’s a novel that reflects its time, yet is also elusive, a chameleon. It can be read as both pro and anti any any category: pro/anti regime, pro/anti intellectual, pro/anti modern, even pro/anti feminist. The slipperiness of the work makes fascinating reflection of its time and a work by a gifted writer.

The story is simple: Mario has died and his wife Maria del Carmen is sitting with his body during the night between the wake and the funeral and recounting their life together. While Carmen does recount their life together, what she is really doing is settling scores. Over twenty-seven chapters she takes him to task for all manner of failings. As she does this a picture of their marriage and Spain emerges. Given the structure of the book it becomes a one sided argument where the reader has create an impression of Mario, but is also given space to agree or disagree with Carmen or Mario. Depending where you stand, some of what Carmen says is disturbing or laughable.

Before I go much farther, a little background would be helpful. From 1939 to 1975 Fransisco Franco ruled the country with a Fascist dictatorship. During the early part of his reign Spain was relatively isolated and poor, but by the early 60’s a growing tourism industry, primary along the beaches of the Mediterranean, and a growing middle class had brought more of a western consumer economy to the country. Consumer goods like the automobiles, especially the SEAT 600 became marks of status and prestige. It’s in this world that Cinco horas takes place.

Before I go much farther, a little background would be helpful. From 1939 to 1975 Fransisco Franco ruled the country with a Fascist dictatorship. During the early part of his reign Spain was relatively isolated and poor, but by the early 60’s a growing tourism industry, primary along the beaches of the Mediterranean, and a growing middle class had brought more of a western consumer economy to the country. Consumer goods like the automobiles, especially the SEAT 600 became marks of status and prestige. It’s in this world that Cinco horas takes place.

Carmen is a good catholic and a solid supporter of the regime (although she’s a monarchist more than a fascist). For her, almost everything about a modernizing Spain is bad: foreign tourists, women wearing pants, children who don’t respect their parents, even the idea of sending girls to the university. Carmen sees the world as a place where you follow the rules, you keep up appearances, and you care about those around you. The book is filled with her diatribes delivered in her stream of conscious grief. Just to give one example, in one memorable moment she says you can tell the difference between a good man and a bad one by the crease in his pants.

While she doesn’t like the changes that are coming to Spain, she does want some of the niceties it’s bringing, particularly a SEAT 600. She returns time and time again to how she is tired of taking the bus, how Mario, an academic, should have enough money to afford a 600. She sees the car not only as a means of transportation, but a symbol of their status. For someone who criticizes Mario for not showing enough grief after his mother died, not because he should grieve, but because one has to keep up appearances, the car is a symbol of everything wrong with Mario.

But who is this Mario? As noted, he was a teacher and intellectual, who wrote novels, was incessantly buying books, and participated in weekly literary salons. He didn’t have much success with his work, and Carmen makes fun of it over and over, mostly because she doesn’t understand it. She’d like to see him write best sellers like everyone else, and then maybe she’d get her 600. Here is the first of the pro/anti debates. To those who like books and literature, Carmen comes off as crude, uninteresting. Yet she is the voice of the novel, and to some extent, of the regime. This is the first on many examples of the slipperiness of the book. Depending on who’s side you take the book has a position for you.

Of course, if the intellectual aspect was the only issue, she wouldn’t have had to spend five house settling scores. Worse than all his intellectual pretensions, were his leftest ideals. Why don’t they have money for a 600? Because he refuses to do what it takes to get ahead. He’s always out for justice for the poor, or as she says, hicks. Over and over she says, if we raise the poor from poverty and educate them, what will happen? Who will be left to raise up. For Carmen, and she says it several times, every one should stay amongst their own kind: the poor with theirs, the tourists (especially Americans) in their own countries, and when it comes to race, Africans should stay in Africa. If Mario was less interested in justice, in her mind something that makes no sense, and a little more accommodating they’d have the car, the apartment with 6 rooms instead of 3 for a family of 7.

She alternatively blames all this adherence to justice to his literary group and his plain stubbornness. She just can’t understand why the poor are so important. And she knows that Mario didn’t crash his bike in the park at 4 AM. He’d been hit on the head by a guard. Mario a truly quixotic figure, wants to make a complaint against the guard. Carmen thinks it’s all laughable. The guard is like the ministry at those hours, she says. But Mario just can’t help but protest. He always has to do the opposite, she says. Again, we have two narratives, and two ways to read the book. Certainly, Carmen holds the regime line. But is Mario brave, a fool, something else?

I mentioned the book might even be read in pro/anti feminist terms. Even though Carmen is very conservative when it comes women’s roles, noting how scandalous it was for her sister to have an illegitimate child with an Italian during the Civil War and then move to Madrid without consequence, at least in her mind, she holds Mario accountable for his sexist behavior. The first glimpse comes when Carmen says girls shouldn’t go to university, a position that Mario holds. While it may seem to be a very conservative position, part of her reasoning is that the men, even those of his literary group, don’t respect women. Even if a woman gets an education, they are only good for sleeping around with or keeping the home. Mario has had an affair with his sister-in-law. There is a memorable scene at the wake when she is more broken up than Carmen. More over, Mario doesn’t respect her. He makes fun of her breast size, won’t let her discipline the children, and generally doesn’t listen to her. She knows that these men, even the one who are full of talk about justice, only want one thing from women. Carmen’s solutions to the problem are certainly debatable, but she knows what’s happening.

One wonders why they got married in the first place. Given that Mario and his family were on the Republican side, or red as Carmen says, why would she marry him. She loved the war, she says, wasn’t afraid, and had the time of her life. She was good, too, was married a virgin. But that didn’t pay off. Mario didn’t respect her, give her love, said on their wedding night, good night, and then turned over. There’s no passion, not like Paco who she knew as a young woman, and now as an older woman has been driven in his Citroen Tibaron, a car classes above the 600. It’s obvious that she is in love with him. The way she describes his eyes, eyes that still look good twenty years after they first met. That he excites her so is something she can’t handle. After complaining about all the things she’s put up with, she begs Mario’s forgiveness for feeling something. She claims she loves Mario, but she doesn’t. It’s Paco, the car, the attention after a loveless marriage, that attracts her.

It’s the interplay between all these impulses, the conservatism, the resentment, the passion that never can be, that makes Cinco horas con Mario work. Moreover, there is a humor at times, one that even seems self depreciating. When Carmen mentions how Mario criticized her breast size she says,

… los intelectuales deberían prohibirles ir a la playa, que así, tan flacos y tan crudios, resultan antiestéticos, más inmorales que los mismos bikinis.

… they should prohibit intellectuals from going to the beach, so thin and under cooked, they turn out antiesthetic, more immoral than bikinis.

Finally, the narration is full of life and idiomatic expressions that make the Cicno horas breathe. When describing how much she like the war she says,

Yo lo pasé fábula, Mario, para qué te voy a contar, toda la ciudad llena de gente, menudo barullo, que todavía no sé, te lo digo sinceramente, cómo no te planté entonces, recién novios, que cada vez venías del frente, con lo de tus hermanos y eso, en plan de revientafiestas, como pensativo, o amaragao, ¡qué sé yo!

It was marvelous, Mario, and I’ll tell you, the whole city full of people, what a racket, that I still don’t know, and I tell you this sincerely, how come you couldn’t hold your ground against them, us newly girlfriend and boyfriend, and every time you came back from the front with your brothers, planing to be a spoil sorts, pensive or bitter, oh, how I know!

Cinco horas con Mario is a complex book that can be read in many different ways. It’s slipperiness that makes it difficult to say exactly which direction Delibes was going when he wrote it. Nevertheless, it is worth of its reputation as a seminal work of 20th century Spanish literature.

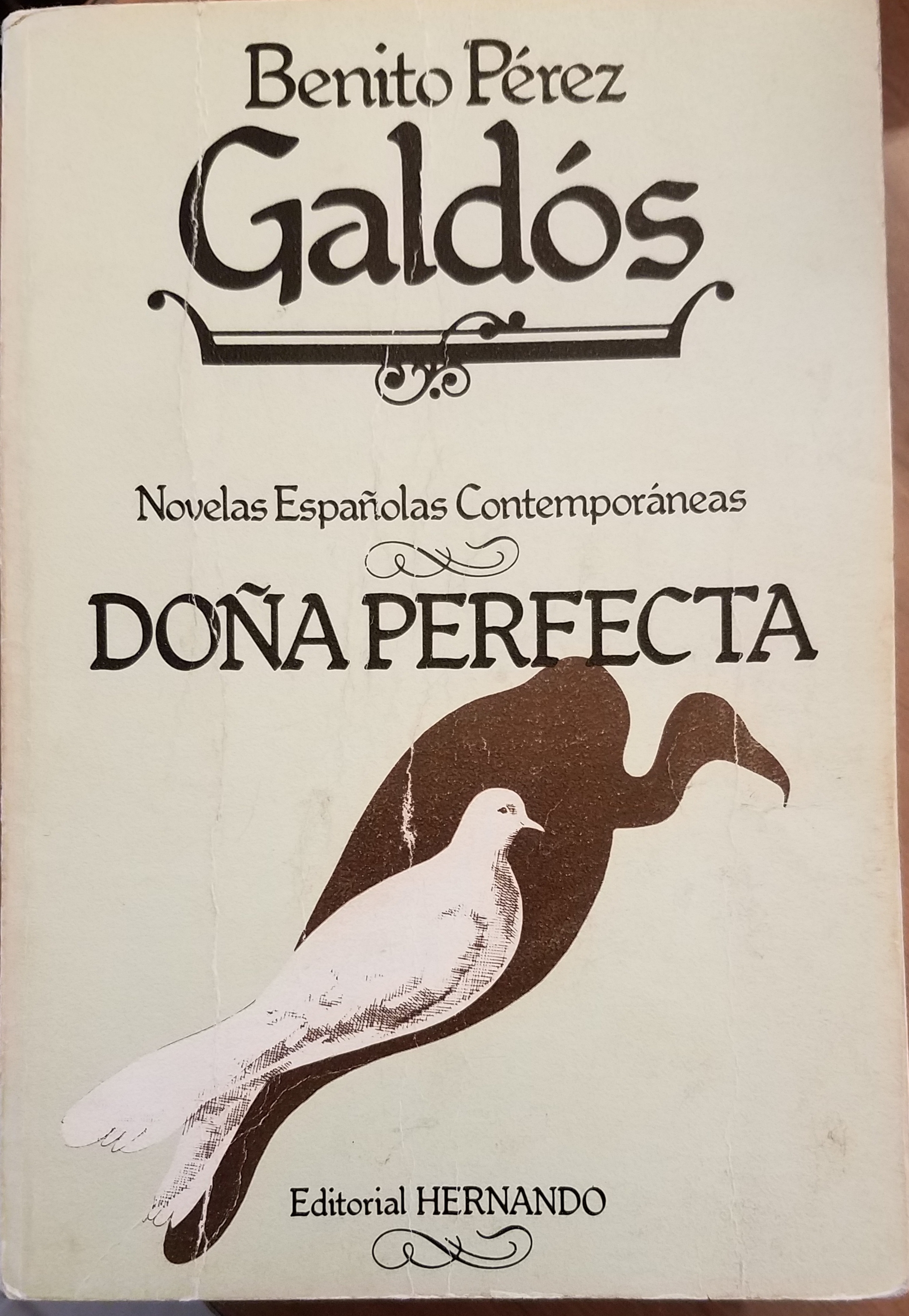

For a country whose most famous literary work is a novel, Doña Perfecta has the appearance of an early novel, a novel whose shifts in style and the occasional lacuna in the plot, suggest a nascent form, one that hasn’t quite come into shape. This, of course, is an error. Benito Pérez Galdós’ 1877 novel is a brilliant work whose structure, style, and themes all seem quite modern, and underscore the struggle between the modern, industrial world of the cities and the conservative, inflexible one of the rural provinces. It is a story, though written nearly 25 years before the start of the twentieth century, presages the internecine battles of the next hundred years.

For a country whose most famous literary work is a novel, Doña Perfecta has the appearance of an early novel, a novel whose shifts in style and the occasional lacuna in the plot, suggest a nascent form, one that hasn’t quite come into shape. This, of course, is an error. Benito Pérez Galdós’ 1877 novel is a brilliant work whose structure, style, and themes all seem quite modern, and underscore the struggle between the modern, industrial world of the cities and the conservative, inflexible one of the rural provinces. It is a story, though written nearly 25 years before the start of the twentieth century, presages the internecine battles of the next hundred years.

Before I go much farther, a little background would be helpful. From 1939 to 1975 Fransisco Franco ruled the country with a Fascist dictatorship. During the early part of his reign Spain was relatively isolated and poor, but by the early 60’s a growing tourism industry, primary along the beaches of the Mediterranean, and a growing middle class had brought more of a western consumer economy to the country. Consumer goods like the automobiles, especially the SEAT 600 became marks of status and prestige. It’s in this world that Cinco horas takes place.

Before I go much farther, a little background would be helpful. From 1939 to 1975 Fransisco Franco ruled the country with a Fascist dictatorship. During the early part of his reign Spain was relatively isolated and poor, but by the early 60’s a growing tourism industry, primary along the beaches of the Mediterranean, and a growing middle class had brought more of a western consumer economy to the country. Consumer goods like the automobiles, especially the SEAT 600 became marks of status and prestige. It’s in this world that Cinco horas takes place. La vuelta al día (Around the Day)

La vuelta al día (Around the Day)