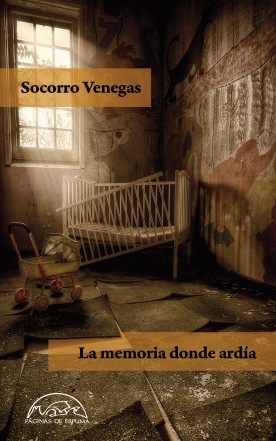

(Where Memory Burns)

Socorro Venegas

Páginas de Espuma, 2019

The Mexican author Socorro Venegas’ fine collection explores the transition to motherhood, the early stages of pregnancy through the first year or so, where doubts, uncertainty, and strictures from outside one’s self and the process, at times, difficult to adjust to. In economical prose (only one story is longer than five pages) she captures in brief moments the encounters that make the transition fraught. Filtering though out the book, explorations of memory as something that both defines and haunts oneself. In the world of La memoria one is constantly confronting what one is trying to escape.

The idea of escape most clear in Pertencias (Belongings) where a young window, overwhelmed by her loss and the ever present reminders of her late husband, she answers an ad in the paper looking for someone to exchange the complete contents of an apartment. In doing so, the narrator completely changes everything around her, including the location of memory, which Venegas rightly locates in physical objects. A beautiful story about grief, she captures the difficulty of the loss itself, but how one is continually reminded of it in subtle ways.

Con su muerte me sucedió algo singular: los que venian a dar me consuelo me confesaban secretos. ¿Veían en mí un filtro muy ancho, por el que también sus penas podrian irse?

With his death something strange happened: those who came to console me could confess their secrets. Did they see in me a wide filter which would also take make their pains go away?

In the comic and fraught La gestión (The Process), a woman who is a few months pregnant is driving in her used car. On the back is a sticker from the previous owner that says “I feel great, ask me how.” A strange man grabs her wrist and won’t let her go until she explains how. The man is insistent, and to diffuse the situation she invites him for coffee at a café across the street. Sitting, watching him, she realizes he is a lost soul, and wonders what his mother was like. But this kind of though is double edged, and plays into her doubts about becoming a mother, and she knows it wasn’t the mother who is at fault.

Que difícil ser madre. No se deja de ser madre nunca, al menos mientras el hijo exista. Por el mundo, en algún sitio, había una mujer entrada en años que parió a este desdichado. Y esa mujer sería siempre cupluda por la infelicidad de su vástago.

It’s so difficult to be a mother. You never stop being a mother, at least while your child exists. Someplace in the world, there was a woman long ago who gave birth to this unfortunate creature. And that woman will always be blamed for the unhappiness of her offspring.

In El hueco (The Gap), Vía lacteca (Milky Way), and Real de catorce, the protagonists, respectively, are living among the difficulties of postpartum depression, loss of a premature baby, and a loss of family control that might also be postpartum depressions. In each she explores the pressure to be the idea mother, or how the perceptions of what motherhood is supposed to be come in conflict with the reality of it. El hueco is particularly dark since there are suggestions that the new mother, once she has given birth, has performed her main duty. Real de catorce, takes that theme and finds a narrator whose husband is “perfect”—he spends more time with the kids than she does—but that perfection is not one of sharing, but, instead, leaves her with tasks that she can only do: cooking, some cleaning. The idea of the helpful spouse is turned on its head, and the narrator is left in the same situation as the mother in El heco, uncertain if she will see her child again. The narrator in Vía lacteca asks, as if in conversation with these other mothers, if becoming a mother was really worth it. In each brief narrative, Venegas captures the complexities of these moments, giving a picture that is anything but happy.

In La soledad en los mapas (The loneliness of maps) a story with echos of the rural villages of Rulfo, two census takers travel to a remote village that is mired in poverty. The town is full of only children: all the parents have left to find work. The pair spend the night together. As the narrator, a woman, is falling asleep she wonders, “Pensé en esos niños tan semejantes a animales, en sus sonrisas fáciles, en sus manos callosas. ¿Niños?” “I thought about the children so similar to animals, about their easy smiles, their calloused hands. Children?” Its a dark vision of childhood. The next morning, covered in bug bites, she asks her partner, if she looks like a pregnant woman, and he says she looks like a castaway. It’s not just among the starkness of the poor village, is the narrator on her own.

Socorro Venegas’ work is marked with subtle insights and an economy of prose that is both elegant and surprising. In the scant 110 pages, she captures so much. An excellent collection.